Reflection – it’s the end of the (transnational adoption) world as we know it

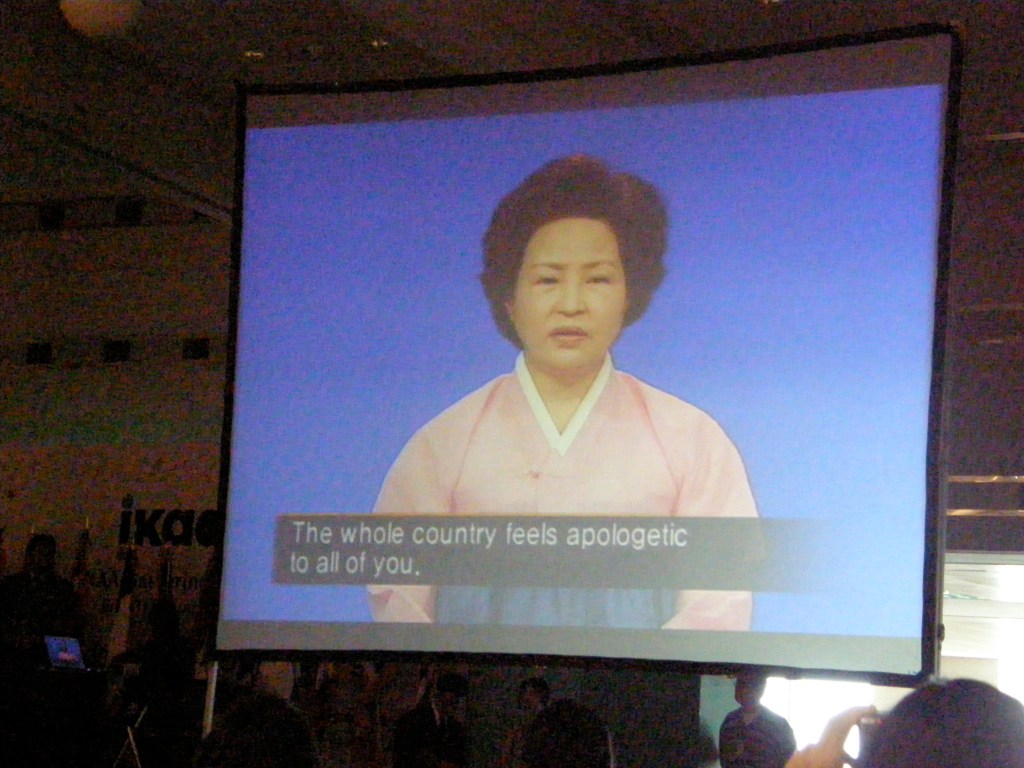

A week ago my phone, email, and social media notifications were flashing and buzzing all day with the news that China had closed their transnational adoption program after more than 30 years and over 160,000 children sent out for adoption (more than 80,000 of them went to the U.S). Then on Monday, the Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission report on corruption in Korea’s adoption program was released. The report confirmed widespread unethical practices including pressuring Korean women into placing their children for adoption, particularly those who were in specific institutions. As I write, I’m working on getting an English translation of the full report.

Some of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report has to do with actions within specific institutions. However, harmful adoption practices in Korea have been widely known for a long time including switching children, coercing expectant mothers, falsifying information, accepting children as “abandoned” without questioning if the person relinquishing was the actual birth mother/parent and confirming consent. Among my Korean adoptee friends and acquaintances I know about agencies who lied to Korean parents who returned to collect their child, believing they had placed them temporarily while the parent was trying to get stable. These parents were told their child had already been sent for adoption (in truth, the child had not yet been sent but would be sent away after lying to the parents). I have friends whose mothers were told their child had died in childbirth. I have friends whose extended family members kidnapped them and brought them to an orphanage or adoption agency. When I went to Korea in 2000 on a birth family search, one of my friends discovered their file had been switched at the adoption agency.

For decades, as Korean adoptees reunited with their Korean first families and learned more about what led up to their adoptions, we have learned about these problematic adoption practices. Yet these stories have been dismissed as one-offs, as a few “bad apples.” Don’t get me started on how much I hate the use of “bad apples” when it comes to adoption – I wrote about this a few years ago.

I appreciate the scrutiny of Korean adoption practices. At the same time, I’m concerned about folks thinking the unethical adoption practices were contained to specific institutions when in reality these institutions were part of larger ideological and systematic practices. It would be easy to focus on these institutions but I hope the investigation looks broadly to the major adoption agencies, their receiving country counterparts, and governmental agents who either actively participated in deceptive adoption practices or looked away.

Some receiving countries have already responded to the increased data on unethical adoptions. Several countries have stopped or are in the process of ending their Korean adoption programs including Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. An investigation in the Netherlands resulted in a full end to all transnational adoptions.

[As an aside, did you know that includes U.S. children? In 2012 it was noted a total of 471 U.S. born children had been adopted to the Netherlands. In 2023, 11 children from the U.S. were sent to the Netherlands for adoption. The ban on foreign adoptions means children from the U.S. will no longer be allowed to be adopted by Dutch families].

I’ve had a few people reach out to ask me how I feel about the news about Korea and China. I’m still processing it but in reality the work I do now is driven by my desire to see adoptions as an unnecessary thing because every single child will be lovingly cared for by their family of origin, making adoption obsolete. I know that won’t happen – for many reasons there will likely always be cases in which children can’t be raised by their original parents. In those cases I sincerely wish for that child to be able to be raised in their family’s extended community when at all possible. Adoption should always be about finding caregivers for a child – I don’t think adoption should ever exist solely to help people become parents.

Based on the trends over the past 15-20 years I believe it’s likely transnational adoption will slow down to a slow trickle but probably won’t end completely. I shed no tears for this potential scenario. One of the reasons I research adoption is to bear witness to our existence, especially for adult adoptees and the communities we’ve created, because I don’t want our existence to only be documented by parents and adoption professionals once it does come to the point where transnational adoptions are a rare, exceptional occurrence. When I think about 20 years from now and the low number of adoptees who will be coming of age, my only desire is to make sure we (the adoptee community) leave something for them, as they’ll be a much smaller group and there may be fewer resources.

So – with apologies to REM, it’s the end of the [transnational adoption] world as we know it. And I feel fine.

For more information, I’m including some links to resources that provide additional context to the news about China and Korea.

- Observant Online article featuring Elvira Loibl, whose research into international adoption found widespread illicit and unethical adoption practices

- Want to learn more about the transnational adoption and the United States? This link will take you to the list of publications from the U.S. State Department. There is a great interactive map available but this map only includes adoptions TO the U.S. so you need to look at the yearly reports to find the OUTGOING adoptions of U.S. born children (such as those I mentioned who were adopted to the Netherlands).

- Some Chinese adoptee adoptee resources

- Navigating Adoption (an organization founded by two Chinese adoptees) is hosting an adoptee-only discussion forum on the end of adoptions from China. The discussion is scheduled for September 17th, 2024 via Zoom. To register, click here.

- China’s Children International

- Red Thread Broken blog/website

- Chinese Adoptee Alliance

- Outsourced Children: Orphanage Care and Adoption in Globalizing China by Leslie K. Wang

- Wanting a Daugher, Needing a Son: Abandonment, Adoption, and Orphanage Care in China by Kay Ann Johnson

- Transnational Adoption: A Cultural Economy of Race, Gender, and Kinship by Sara Dorow

- Some Korean adoptee resources

- International Korean Adoptee Association

- I’ve included a list of some Korean adoptee groups around the world here

- To Save the Children of Korea: The Cold War Origins of International Adoption by Arissa Oh

- Invisible Asians: Korean American Adoptees, Asian American Experiences and Racial Exceptionalism by Kim Park Nelson

- Adopted Territory: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Politics of Belonging by Eleana J. Kim.

- International Korean Adoption: A Fifty-year History of Policy and Practice by Kathleen Ja Sook Bergquist, M. Elizabeth Vonk, Dong Soo Kim and Marvin D. Feit

- Disrupting Kinship: Transnational Politics of Korean Adoption in the United States by Kimberly McKee

Thanks for this clear-eyed assessment. A Frontline documentary, “South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning,” will be airing on PBS on Sept. 20, and will be available to stream after that date on their website and youtube channel. I hope it will be another nail in the coffin for intercountry adoption.

As always JaeRan you offer a thoughtful, accurage and insightful reflection. So appreciate your voice in the field of adoption!